Subversion of Juries

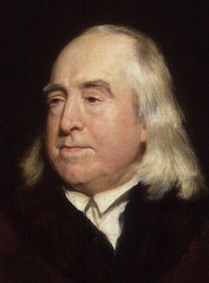

Sir William BLACKSTONE SL KC (1723-1780)

English jurist, judge and MP

“So that the liberties of England cannot but subsist so long as this palladium remains sacred and inviolate; not only from all open attacks (which none will be so hardy as to make), but also from all secret machinations, which may sap and undermine it; by introducing new and arbitrary methods of trial; by justices of the peace, commissioners of the revenue, and courts of conscience. And however convenient these may appear at first (as doubtless all arbitrary powers, well executed, are the most convenient), yet let it be again remembered, that delays and little inconveniences in the forms of justice, are the price that all free nations must pay for their liberty in more substantial matters; that these inroads upon this sacred bulwark of the nation are fundamentally opposite to the spirit of our constitution; and that, though begun in trifles, the precedent may gradually increase and spread, to the utter disuse of juries in questions of the most momentous concern.”

Sir William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England

Factors Undermining Jury Power

The 19th century saw the beginning of fundamental reforms to the legal system. Bit by bit fresh duties of a judicial character were heaped upon Justices of the Peace (JPs) by various Statutes and police forces were formed. Acts of Parliament thus immeasurably extended the common-law powers of justices whilst at the same duplicating and slowly undermining the established role of both the Grand and Petit Jury.

For those opposed to the Grand Jury the Justice of the Peace had all but slowly rendered the grand jury superfluous.

For those opposed to the Grand Jury the Justice of the Peace had all but slowly rendered the grand jury superfluous.

i. Stipendiary Magistrates

Over centuries unpaid Justices of the Peace had conducted arraignments in all criminal cases and tried misdemeanours of local laws. Towns and boroughs that could not find volunteers had to petition the Crown for authority to hire a paid Stipendiary Magistrate.

In 1792 Stipendiary Magistrates were established in London. In 1813 a Stipendiary Magistrate was appointed for Manchester and later legislation provided for boroughs and urban areas to request the appointment of a stipendiary (1835). The 1863 Stipendiary Magistrates Act enabled cities, towns and boroughs to obtain the appointment of stipendiary magistrates - a trained lawyer who was able to hear cases alone.

It has been noted that there were initially very few appointments, suggesting the public preferred justice to be administered by lay magistrates than by lawyers. Stipendiary Magistrates were replaced by District Judges in 2000.

Over centuries unpaid Justices of the Peace had conducted arraignments in all criminal cases and tried misdemeanours of local laws. Towns and boroughs that could not find volunteers had to petition the Crown for authority to hire a paid Stipendiary Magistrate.

In 1792 Stipendiary Magistrates were established in London. In 1813 a Stipendiary Magistrate was appointed for Manchester and later legislation provided for boroughs and urban areas to request the appointment of a stipendiary (1835). The 1863 Stipendiary Magistrates Act enabled cities, towns and boroughs to obtain the appointment of stipendiary magistrates - a trained lawyer who was able to hear cases alone.

It has been noted that there were initially very few appointments, suggesting the public preferred justice to be administered by lay magistrates than by lawyers. Stipendiary Magistrates were replaced by District Judges in 2000.

ii. The Emergence of Police Forces

In 1829 the Metropolitan Police Act established a police force in London responsible for the prosecution of suspected criminals. Acts of Parliament in 1835 and 1839 allowed first borough councils and then English counties to organise police forces. Policing was made compulsory throughout England and Wales with the 1856 County and Borough Police Act.

In 1829 the Metropolitan Police Act established a police force in London responsible for the prosecution of suspected criminals. Acts of Parliament in 1835 and 1839 allowed first borough councils and then English counties to organise police forces. Policing was made compulsory throughout England and Wales with the 1856 County and Borough Police Act.

iii. The Prisoners' Counsel Act

The 1836 Prisoners' Counsel Act has been described as the most significant development in trial procedure during the nineteenth century. This Act granted prisoners accused of serious crimes the right to delegate presentation of their defence to a professional counsel.

Before the Act prisoners could only use advocates to examine and cross examine witnesses at the discretion of the trial judge. They could only defend their case themselves in what has been termed the 'Accused speaks’ form of trial. It was the commonly held view that the innocent accused was in the best position to defend themselves in court. In practice the Act embedded the defence counsel as a permanent fixture of the felony trial.

There are two main reasons to explain why the Act was passed: the first concerns the inevitable consequence that Barristers and Solicitors were bound to make a lot of money from the ‘lawyerisation’ of the legal process. The second was that it forms part and parcel of Benthamite influence upon the development of government and law during that period in history.

The 1836 Prisoners' Counsel Act has been described as the most significant development in trial procedure during the nineteenth century. This Act granted prisoners accused of serious crimes the right to delegate presentation of their defence to a professional counsel.

Before the Act prisoners could only use advocates to examine and cross examine witnesses at the discretion of the trial judge. They could only defend their case themselves in what has been termed the 'Accused speaks’ form of trial. It was the commonly held view that the innocent accused was in the best position to defend themselves in court. In practice the Act embedded the defence counsel as a permanent fixture of the felony trial.

There are two main reasons to explain why the Act was passed: the first concerns the inevitable consequence that Barristers and Solicitors were bound to make a lot of money from the ‘lawyerisation’ of the legal process. The second was that it forms part and parcel of Benthamite influence upon the development of government and law during that period in history.

Bentham vs. Mill

The basic presupposition of Jeremy Bentham (underpinned by his philosophy of 'utilitarianism') was that the growth of what has come to be known as the ‘administrative state’ was a virtually inevitable consequence of society becoming more scientifically rational.

This supposedly coldly analytical approach to law was met with much scepticism, not least from John Stuart Mill, whose version of utilitarianism aspired to include a more ethical approach.

In his work on ‘The Influence of Lawyers’ (1827) Mill claimed that such influence was ‘pernicious to morals, jurisprudence and government’ because lawyers were immoral whichever side - for or against justice - they represented due to the pecuniary interest they had in the outcome of a trial.

The basic presupposition of Jeremy Bentham (underpinned by his philosophy of 'utilitarianism') was that the growth of what has come to be known as the ‘administrative state’ was a virtually inevitable consequence of society becoming more scientifically rational.

This supposedly coldly analytical approach to law was met with much scepticism, not least from John Stuart Mill, whose version of utilitarianism aspired to include a more ethical approach.

In his work on ‘The Influence of Lawyers’ (1827) Mill claimed that such influence was ‘pernicious to morals, jurisprudence and government’ because lawyers were immoral whichever side - for or against justice - they represented due to the pecuniary interest they had in the outcome of a trial.

Concerns of Parliament

A major concern voiced in Parliament about the Act was the assumption that should defence counsel be allowed to speak on the prisoner’s behalf, the felony trial would become a verbal gladiatorial arena. Criticism directly related to this concern was raised over twenty times between 1821 and 1836 in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. One MP claimed the reforms would: "change the sober floor of a court of justice into an arena for two ingenious combatants to display their strength and agility in; the stake for which they played being nothing less than the life of a man".

Many believed the replacement of the ‘Accused speaks’ trial by the adversarial lawyerised trial could replace the authentically direct testimony of the accused by a system allowing for the manipulation of testimony by counsel which could undermine the quality of the evidence presented in court.

Throughout the Parliamentary debates repeated references were made to the public’s low opinion of legal counsel. In 1824, even one of the foremost early advocates of the reforms, George Lamb, admitted that public satisfaction with trials would be improved if there was no counsel at all, prosecuting or defending. In essence this view vindicated the standpoint made half century earlier by John Horne Tooke during one of his trials, where he made clear that the Plaintiff, the Defendant and the Jury were the only three essential parties at a trial. The judge was present only as an assistant.

(See the reference to Horne Tooke under 1794 Treason Trials).

A major concern voiced in Parliament about the Act was the assumption that should defence counsel be allowed to speak on the prisoner’s behalf, the felony trial would become a verbal gladiatorial arena. Criticism directly related to this concern was raised over twenty times between 1821 and 1836 in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. One MP claimed the reforms would: "change the sober floor of a court of justice into an arena for two ingenious combatants to display their strength and agility in; the stake for which they played being nothing less than the life of a man".

Many believed the replacement of the ‘Accused speaks’ trial by the adversarial lawyerised trial could replace the authentically direct testimony of the accused by a system allowing for the manipulation of testimony by counsel which could undermine the quality of the evidence presented in court.

Throughout the Parliamentary debates repeated references were made to the public’s low opinion of legal counsel. In 1824, even one of the foremost early advocates of the reforms, George Lamb, admitted that public satisfaction with trials would be improved if there was no counsel at all, prosecuting or defending. In essence this view vindicated the standpoint made half century earlier by John Horne Tooke during one of his trials, where he made clear that the Plaintiff, the Defendant and the Jury were the only three essential parties at a trial. The judge was present only as an assistant.

(See the reference to Horne Tooke under 1794 Treason Trials).

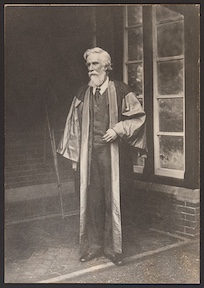

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (1747 - 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism. He was a pupil of Blackstone at Oxford yet regarded Blackstone as the arch-enemy (GM Trevelyan). He attacked the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 and criticised the recognition of ‘self-evident truths.’ Bentham was the first person to aggressively advocate for the codification of all of the common law into a coherent set of statutes.

Bentham opened the attack on the grand jury early in the 19th century. He objected to the grand jury because of its secrecy which he alleged prejudiced the accused who was unrepresented and unheard.

“A jury is a good thing; a grand jury is a jury, ergo, a grand jury is a good thing. . . . Such being the logic ...it is necessary to show what sort of a thing a grand jury really is. . . . A grand jury is a bar to penal justice. . . . Whatever it may have been at one time, as matters have stood for a long time, a grand jury has been, is, and will be, an instrument worse than useless. . . . They once had an object, but that object has been done away; it might be seen to be so, if bigotry had eyes; but bigotry is blind; the incumbrance keeps its place; lawyers and their dupes never speak of it but with rapture."

Jeremy Bentham (1747 - 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism. He was a pupil of Blackstone at Oxford yet regarded Blackstone as the arch-enemy (GM Trevelyan). He attacked the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 and criticised the recognition of ‘self-evident truths.’ Bentham was the first person to aggressively advocate for the codification of all of the common law into a coherent set of statutes.

Bentham opened the attack on the grand jury early in the 19th century. He objected to the grand jury because of its secrecy which he alleged prejudiced the accused who was unrepresented and unheard.

“A jury is a good thing; a grand jury is a jury, ergo, a grand jury is a good thing. . . . Such being the logic ...it is necessary to show what sort of a thing a grand jury really is. . . . A grand jury is a bar to penal justice. . . . Whatever it may have been at one time, as matters have stood for a long time, a grand jury has been, is, and will be, an instrument worse than useless. . . . They once had an object, but that object has been done away; it might be seen to be so, if bigotry had eyes; but bigotry is blind; the incumbrance keeps its place; lawyers and their dupes never speak of it but with rapture."

A.V. Dicey

A.V. Dicey, long recognised as a major constitutional theorist of British law quoted repeatedly still in Parliament, held Jeremy Bentham in high regard.

Dicey is the main theorist to have claimed that Parliament is the highest form of sovereign power in the UK constitution He originated the term 'rule of law' which by his reckoning almost certainly ruled out the principle of jury nullification.

Oxford Professor Dicey chose to become the first Professor of Law at the then newly founded LSE. He was consequently both aligned with and approved by its founder: The Fabian Society.

Consequently Dicey's influence stands counterposed to that of John Lilburne in regard to the importance of jury power in the British and more especially American Constitutions. This helps explain the subversion of such power up to and including the abolition of the British Grand Jury in 1933.

A.V. Dicey, long recognised as a major constitutional theorist of British law quoted repeatedly still in Parliament, held Jeremy Bentham in high regard.

Dicey is the main theorist to have claimed that Parliament is the highest form of sovereign power in the UK constitution He originated the term 'rule of law' which by his reckoning almost certainly ruled out the principle of jury nullification.

Oxford Professor Dicey chose to become the first Professor of Law at the then newly founded LSE. He was consequently both aligned with and approved by its founder: The Fabian Society.

Consequently Dicey's influence stands counterposed to that of John Lilburne in regard to the importance of jury power in the British and more especially American Constitutions. This helps explain the subversion of such power up to and including the abolition of the British Grand Jury in 1933.

iv. Jervis Acts

In 1848 Attorney General Sir John Jervis guided three Acts through Parliament known collectively as the Jervis Acts:

Indictable Offences Act

Summary Jurisdiction Act

Justices Protection Act

Criminal Cases

At the beginning of the 19th century criminal cases were classed as either indictable or non-indictable offences.

The 1848 Summary Jurisdiction Act led to a vast increase in summary jurisdiction and marked the first inroad into removing the right to trial by jury.

Alongside indictable and summary offences, either way offences were introduced whereby a defendant could chose the method of trial. The scales were weighted in favour of a summary trial because committal was often spent waiting in prison and conviction by jury meant a longer sentence. After 1848 defendants were encouraged to plead guilty in front of a magistrate rather than risk being found guilty by a jury and getting a longer sentence.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries further Acts of Parliament steadily increased the number of offences triable without a jury. Either way triable offences were extended by both increasing the range of offences covered and raising the limit of fines payable. In 1977 the sentencing power of magistrates was increased from six to twelve months.

The 1848 Justices Protection Act gave JPs and Stipendiary Magistrates immunity from civil actions arising from their adjudications and separated them from all police functions.

It also expanded the role of magistrates in pre-trials. Rules were established for holding a preliminary public examination of those alleged to have committed a crime with both sides, defendant and prosecutor, being represented and heard. These examinations undermined further the role of the Grand Jury as a check on groundless prosecutions.

Civil Cases

Common law civil cases were tried by jury until juryless trials were introduced into the new County Courts in 1846.

The option of trial by judge alone was extended by the Common Law Procedure Act in 1854 and over the following decades the use of juries in civil trials has steadily declined until they have been almost entirely eradicated.

In 1848 Attorney General Sir John Jervis guided three Acts through Parliament known collectively as the Jervis Acts:

Indictable Offences Act

Summary Jurisdiction Act

Justices Protection Act

Criminal Cases

At the beginning of the 19th century criminal cases were classed as either indictable or non-indictable offences.

The 1848 Summary Jurisdiction Act led to a vast increase in summary jurisdiction and marked the first inroad into removing the right to trial by jury.

Alongside indictable and summary offences, either way offences were introduced whereby a defendant could chose the method of trial. The scales were weighted in favour of a summary trial because committal was often spent waiting in prison and conviction by jury meant a longer sentence. After 1848 defendants were encouraged to plead guilty in front of a magistrate rather than risk being found guilty by a jury and getting a longer sentence.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries further Acts of Parliament steadily increased the number of offences triable without a jury. Either way triable offences were extended by both increasing the range of offences covered and raising the limit of fines payable. In 1977 the sentencing power of magistrates was increased from six to twelve months.

The 1848 Justices Protection Act gave JPs and Stipendiary Magistrates immunity from civil actions arising from their adjudications and separated them from all police functions.

It also expanded the role of magistrates in pre-trials. Rules were established for holding a preliminary public examination of those alleged to have committed a crime with both sides, defendant and prosecutor, being represented and heard. These examinations undermined further the role of the Grand Jury as a check on groundless prosecutions.

Civil Cases

Common law civil cases were tried by jury until juryless trials were introduced into the new County Courts in 1846.

The option of trial by judge alone was extended by the Common Law Procedure Act in 1854 and over the following decades the use of juries in civil trials has steadily declined until they have been almost entirely eradicated.

Common Law: based on legal precedent made by judges and juries. Built on case law it is constantly changing.

Statutory Law: based on Acts of Parliament, Regulations and By-laws.

Indictable offences: triable before a jury.

Non-Indictable offences: triable before Justices of the Peace without a jury.

Summary offences: heard by a judge or magistrate without a jury. They are based entirely on statutory law and date from 1848-49.

Statutory Law: based on Acts of Parliament, Regulations and By-laws.

Indictable offences: triable before a jury.

Non-Indictable offences: triable before Justices of the Peace without a jury.

Summary offences: heard by a judge or magistrate without a jury. They are based entirely on statutory law and date from 1848-49.

Sir John Jervis (1802-1856)

Lawyer and judge. He was Attorney-General during the European revolutions of 1848 and was responsible for bringing prosecutions against Chartists under the 1848 Treason Felony Act.

v. Director of Public Prosecutions

In 1879 the Prosecution of Offences Act created the first Director of Public Prosecutions. As part of the Home Office the Director took on a small number of difficult or important cases. However the police remained responsible for the majority of prosecutions and the rights of private prosecutors were preserved.

In 1879 the Prosecution of Offences Act created the first Director of Public Prosecutions. As part of the Home Office the Director took on a small number of difficult or important cases. However the police remained responsible for the majority of prosecutions and the rights of private prosecutors were preserved.

Pre 1879 there was no provision for the systematic prosecution of offences in England. Prosecutions were initiated by injured parties unless a matter of public importance was involved and the Attorney General could initiate a case.

The Office of Public Prosecutions was established in 1908.