1794 Treason Trials

Although the majority of the British population had no right to vote, the influence of public opinion was strong. Radical organisations often focused on demands for parliamentary reform and extending the right to vote.

Most politicians were satirised in cartoons and there was a huge market for political pamphlets, books, ballads and newspapers. One such radical publication was the North Briton started by John Wilkes in 1762.

In 1763 John Wilkes was charged with seditious libel after publishing an article in The North Briton attacking George III's speech endorsing the Paris Peace Treaty.

Forty-nine people, including Wilkes, were arrested under general warrants. These warrants named no specific person, place, or thing to be searched or seized and were very unpopular. In his defence Wilkes asserted their unconstitutionality and invoked the ancient liberties guaranteed by Magna Carta.

At his court hearing he claimed that parliamentary privilege protected him, as an MP, from arrest on a charge of libel. The Lord Chief Justice ruled that parliamentary privilege did indeed protect him and he was soon restored to his seat. Parliament swiftly voted in a measure that removed protection of MPs from arrest for the writing and publishing of seditious libel.

Following his release Wilkes was presented with a copy of Lilburne’s 1649 trial and the medallion commemorating it.

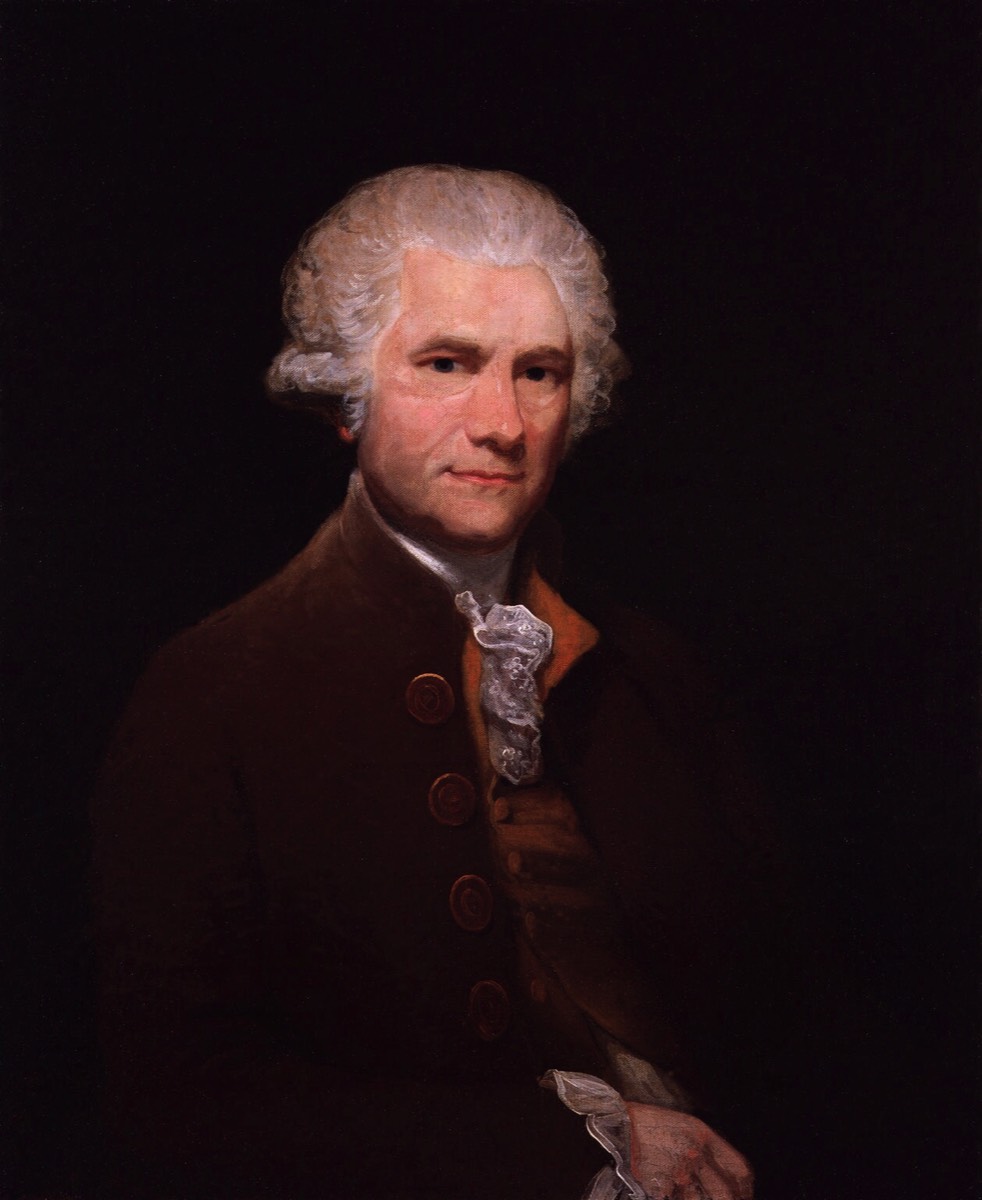

John Wilkes (1725-1797)

English radical journalist, politician, magistrate

and soldier.

John Horne Tooke

John Horne Tooke (1736-1812)

Clergyman, politician and philologist

John Horne Tooke was a founding member of the Society of Supporters of the Bill of Rights established in 1769 to aid John Wilkes and to press for parliamentary reform. He later became a founding member of the Society for Constitutional Information and wrote the Constitution for the London Corresponding Society.

He was held in high regard by Thomas Paine as the most trustworthy advocate of American independence. Horne Tooke was the only British subject to be imprisoned for supporting the American Revolution.

Thomas Jefferson met Horne Tooke and referred to him as an ‘associate in persecution’ of John Baxter, author of a book on the History of England which was aimed at debunking David Hume’s work on that subject which he had written partly in order to cast doubt upon the ‘whig’ viewpoint. This disagreement between Hume and Baxter touched upon fundamental differences that had arisen in the English Civil War. At the heart of the conflict were counterpoising views of the role of common law, jury powers and England’s ‘ancient constitution.’

Jefferson held Baxter’s work in very high regard over and above Hume’s analysis and wanted to establish it as the main text book on English history in the USA.

Horne Tooke was certainly in full accord with the approach taken by the Levellers to jury power. During one of his several trials he described the role of the jury as follows:

“In the performance of this duty to our country, I must beg you to observe, and carefully to remember it to the end, that there are only three efficient and necessary parties… the Plaintiff… the Defendant; and you, gentlemen, the Jury. The judge and the cryer of the court attend alike in their respective situations; and they are paid by us for their attendance; we pay them well; they are hired to be the assistants and reporters, but they are not, and they never were intended to be the controllers of our conduct… A Jury not entitled to inquire into the merits of the question brought before them, nor into anything that relates to the merits, is no Jury at all.”

These insights provided by Horne Tooke are fully consistent with the great victories for jury power won by Lilburne and to this day continue to throw a critical light upon anti-democratic tendencies within legal and academic professions. Later in mid-19th century USA Lysander Spooner further emphasised the full merits of jury power by clarifying in detail why the decision making processes of juries are considerably more complex and astute than judicial elitists would have the public believe.

The 1794 treason trials formed part of a government campaign to destroy the remnants of 17th century British radical democracy that had enjoyed a resurgence in the wake of the American and French Revolutions.

Reform organisations such as the London Corresponding Society and the Society for Constitutional Information had rapidly increased their membership in the early 1790s.

The government responded first with the sedition trials of Thomas Paine, John Frost and Daniel Isaac Eaton in 1792–3 and then with the treason trials of 1794.

On 12 May 1794 more than thirty leading radicals, including John Thelwall, Thomas Holcroft, John Horne Tooke, Thomas Hardy, and Thomas Spence were arrested. Following an examination of papers seized during the arrests, the government moved to suspend habeas corpus on 23 May. As a result, the men arrested on suspicion of high treason could be held without charge until the spring of 1795.

Initially, the men were held in the Tower of London before being moved to Newgate Prison. After several months, a number of those arrested were formally charged with high treason. If convicted they could be hanged, drawn and quartered.

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was founded by Thomas Hardy and was active between 1792–1799.

The LCS was primarily conceived as a working-class forum for tradesmen, mechanics, and shopkeepers. As Hardy once asserted, the LCS was to represent those who were 'but few in number and humble in situation and circumstances'.

The activities of the LCS were a great concern to the government, which employed an intricate network of spies to infiltrate the society.

The Society for Constitutional Information (active 1780–1794) was founded to promote parliamentary reform. It was an organisation dedicated to publishing political tracts aimed at educating fellow citizens on their lost ancient liberties.

The organisation actively promoted Thomas Paine's Rights of Man and other campaigners for parliamentary reform. Most members of the Society for Constitutional Information were also opposed to the slave trade.

Thomas Hardy (1752-1832)

An early radical and the founder, first Secretary and Treasurer of the London Corresponding Society

The trial of Thomas Hardy, Secretary of the London Corresponding Society, began on 28 October 1794.

As E.P. Thompson states: “Thelwall, Hardy, and ten other prisoners were committed to the Tower and later to Newgate. While there Thelwall was for a time confined in the charnel-house; and Mrs Hardy died in childbirth as a result of shock sustained when her home was besieged by a ‘Church and King’ mob... A Grand Jury of Respectable Citizens had no stomach for this. After a nine-day trial Hardy was acquitted. The foreman of the jury fainted after delivering his ‘not guilty’ while the London crowd went wild with enthusiasm and dragged Hardy in triumph through the streets.”

John Thelwall

Two further trials of John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall also resulted in jury acquittals and as a result all of the other cases were dismissed including that against the author John Baxter.

John Thelwall (1764-1834)

Journalist and writer who sought political reforms in Britain, including universal suffrage, annual elections for Parliament and freedom of association. Member of the London Corresponding Society. In later life he lived in Wales and it has been suggested he may have been involved in the agitation leading up to the Merthyr Rising in 1831 led by steel workers, very possibly the first working class rebellion in history.

E.P. Thompson designates two main periods in the development of the early working class movement: the illegal period up to the defeat of the French Empire followed by the ‘heroic’ period leading up to the main campaigns of the Chartists for expanding the suffrage.

The 1794 treason trials were followed most significantly by those of 38 radical reformers who were found not guilty of taking illegal oaths in 1812.

There followed the Peterloo Massacre in which 18 protesters were killed and hundreds injured when cavalry charged their demonstration for the right to vote.

Largely in response to this an armed attempt at seizing control of the Westminster Government took place in central London known as the ‘Cato Street Conspiracy.’ Its leaders declared their right to resist tyranny in accordance with Magna Carta but were tried with some executed and others deported to Australia.

That same year, a medal commemorating the constitutional aims of the radical movement was struck. It included the Grand Jury as a necessary institution of a just constitution.