The 17th Century Civil Wars

Alexis De Tocqueville (1805-1859) commented that during the Tudor period the civil jury saved the liberties of England.

The importance of the both the Petit Jury and Grand Jury in defending the people against the oppression and despotism of the Crown was firmly established during the 17th century.

Court of Star Chamber

The Star Chamber was a court from the late 15th to the mid-17th century composed of Privy Counsellors and common-law judges. It was a court of appeal, a supervisory body overseeing the operation of the lower courts, and could hear cases by direct appeal as well.

Initially well regarded it was established to ensure the fair enforcement of laws against socially and politically prominent people sufficiently powerful that ordinary courts might hesitate to convict them of their crimes. However, it became synonymous with social and political oppression through the arbitrary use and abuse of the power it wielded.

The court could impose punishment for actions which were deemed to be morally reprehensible but were not in violation of the letter of the law. This gave the Star Chamber great flexibility, as it could punish defendants for any action which the court felt should be unlawful, even when in fact it was technically lawful. Crimes such as conspiracy, criminal libel, and perjury, were originally developed by the Court of Star Chamber, along with its more common role of dealing with riots and sedition.

The importance of the both the Petit Jury and Grand Jury in defending the people against the oppression and despotism of the Crown was firmly established during the 17th century.

Court of Star Chamber

The Star Chamber was a court from the late 15th to the mid-17th century composed of Privy Counsellors and common-law judges. It was a court of appeal, a supervisory body overseeing the operation of the lower courts, and could hear cases by direct appeal as well.

Initially well regarded it was established to ensure the fair enforcement of laws against socially and politically prominent people sufficiently powerful that ordinary courts might hesitate to convict them of their crimes. However, it became synonymous with social and political oppression through the arbitrary use and abuse of the power it wielded.

The court could impose punishment for actions which were deemed to be morally reprehensible but were not in violation of the letter of the law. This gave the Star Chamber great flexibility, as it could punish defendants for any action which the court felt should be unlawful, even when in fact it was technically lawful. Crimes such as conspiracy, criminal libel, and perjury, were originally developed by the Court of Star Chamber, along with its more common role of dealing with riots and sedition.

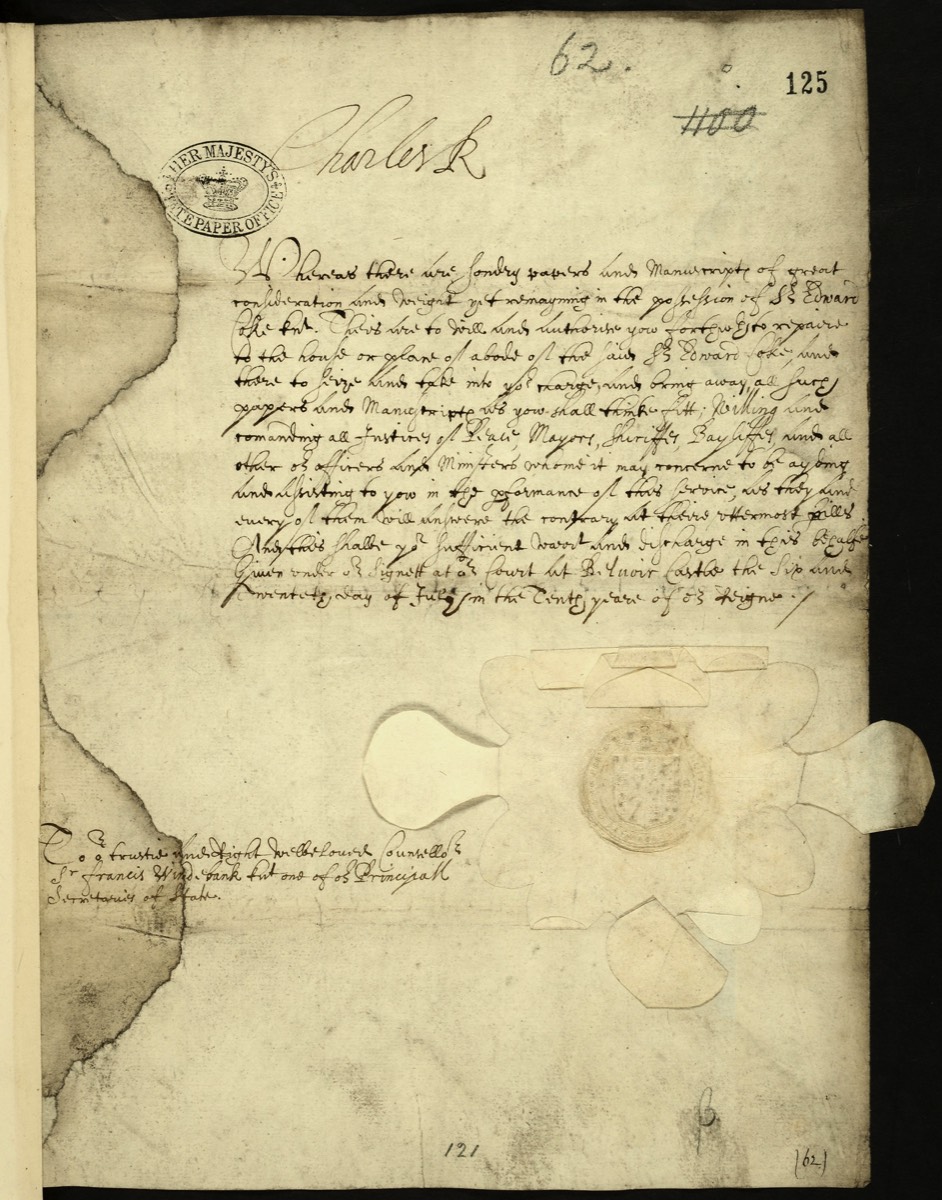

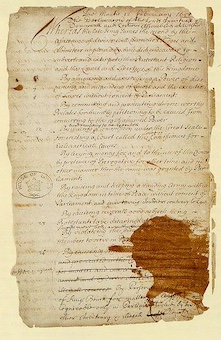

Letter from King Charles authorising the confiscation of Coke’s papers (1634)

© The National Archives, London

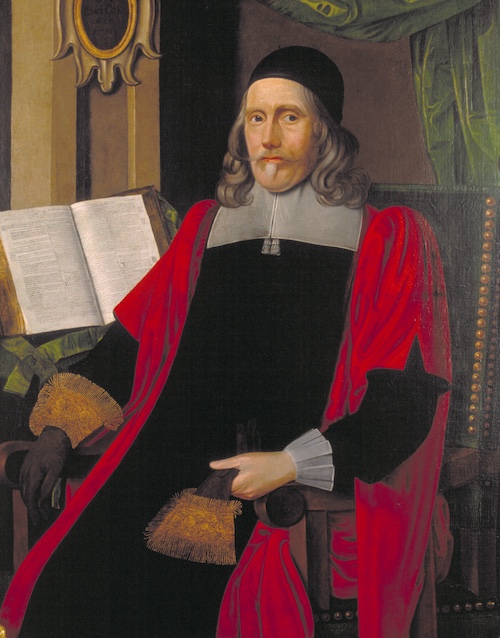

Sir Edward Coke

Sir Edward Coke defended the supremacy of the common law against Stuart claims of royal prerogative. He had a profound influence on the development of English law and the English constitution.

As Chief Justice, Coke restricted the use of the Star Chamber oath and, in the Case of Proclamations and Dr. Bonham's Case, declared the King to be subject to the law, and the laws of Parliament to be void if in violation of "common right and reason".

Coke surmised that ‘Judgements given against any points of the Charters of Magna Carta or the Charter of the Forest are adjudged void and... if any statute be made against either of these charters it shall be void.’

As a result Coke was dismissed as Chief Justice by King James I in 1616.

In 1628 Coke published the first volume of his Institutes of the Lawes of England. The final three volumes of his work appeared only posthumously because the manuscripts were confiscated on the orders of Charles I, an action prompted by Coke’s Second Institute which included an extensive clause-by-clause analysis of Magna Carta. It was finally printed in 1642 on the eve of the English Civil Wars.

Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634)

British jurist and Politician

1628 Petition of Right

In 1628 Edward Coke drafted The Petition of Right, described by Geoffrey Robertson QC as an updated version of Magna Carta.

It drew attention to a series of breaches of law in violation of the spirit of Magna Carta and was sent to King Charles I by the English Parliament. Re-affirming Magna Carta and habeas corpus the Petition of Right sought recognition of four principles: no taxation without the consent of Parliament, no imprisonment without cause, no quartering of soldiers on subjects, and no martial law in peacetime.

In 1628 Edward Coke drafted The Petition of Right, described by Geoffrey Robertson QC as an updated version of Magna Carta.

It drew attention to a series of breaches of law in violation of the spirit of Magna Carta and was sent to King Charles I by the English Parliament. Re-affirming Magna Carta and habeas corpus the Petition of Right sought recognition of four principles: no taxation without the consent of Parliament, no imprisonment without cause, no quartering of soldiers on subjects, and no martial law in peacetime.

By presenting a ‘Petition of Right’, rather than a formal bill, the Commons were claiming existing rights, rather than creating new ones.

King Charles I was compelled to accept the petition though he later ignored its principles. Nevertheless the Petition of Right came to be regarded as a constitutional document of the government of the United Kingdom, alongside the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights.

The Jury as Judge of Law and Fact

In 1639, after eleven years of absence, Charles I was forced to recall Parliament to vote him money for his war against the Scots. When Charles I refused demands by Puritan MPs for a share in power civil war ensued (1642 - 1651).

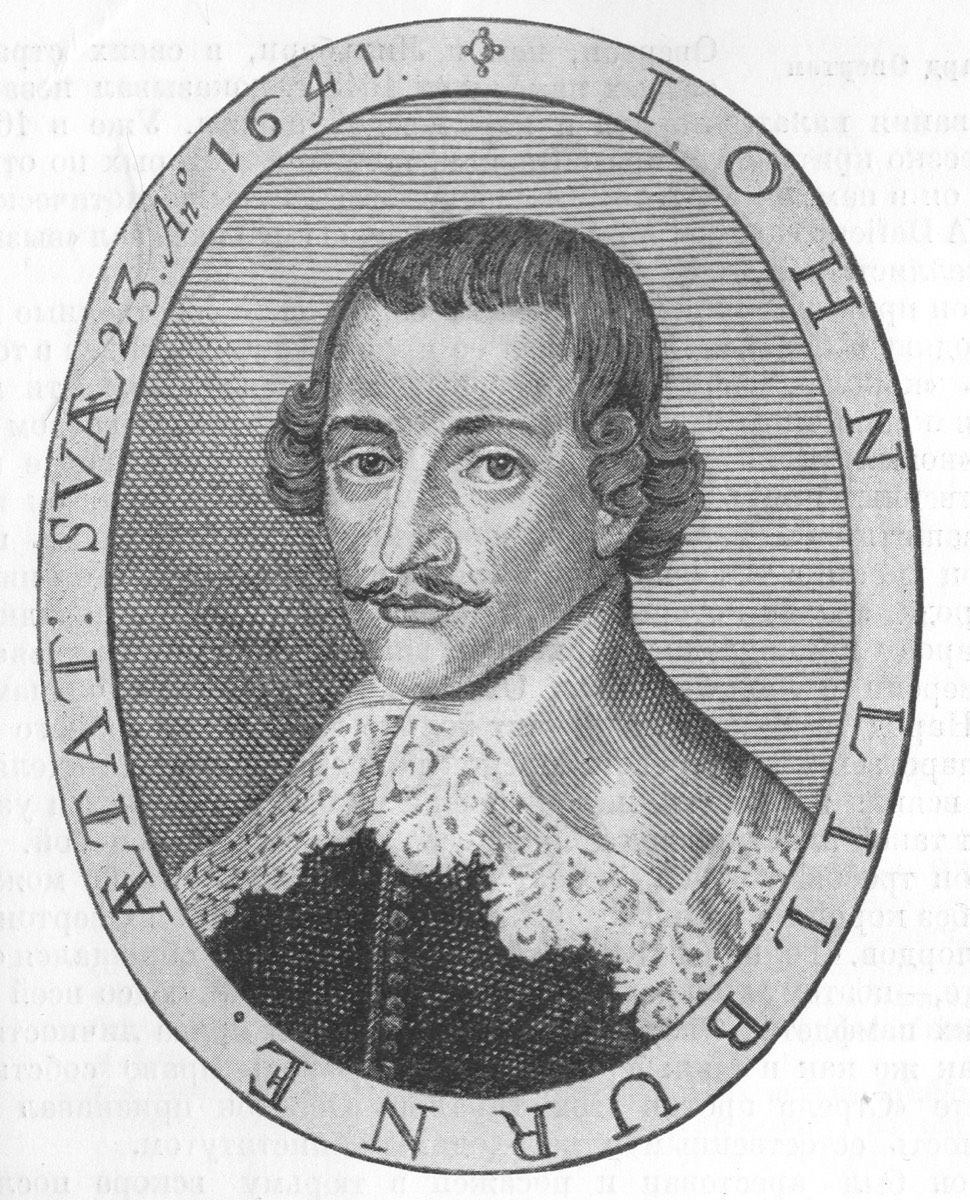

John Lilburne

John Lilburne was a politically active London apprentice who initially sought greater toleration from the Crown for the Puritan cause in 1639. He was tried by the usually juryless Star Chamber, imprisoned, flogged and placed in pillory stocks after he defended his rights in accordance with the teachings of Edmund Coke. His arguments later got support from Parliament and were decisive in abolishing the Star Chamber by means of the Habeus Corpus Act of 1640.

Lilburne served as a Lieutenant Colonel in the civil war. After King Charles I was defeated in the first civil war Lilburne, by then a Lt .Colonel, became leader of the ‘Levellers’ and sought more broadly based religious toleration and an end to parliamentary corruption. He was the chief author of the Levellers Agreement of the People which in effect challenged the claim that Parliament is the sole representative of the people in the English constitution.

Lilburne argued that English subjects are ’freeborn’ with individual liberties enshrined in Magna Carta. Despite this Parliament later imprisoned him for opposing Cromwell’s attempt to impose an exclusively Presbyterian constitution through his alliance with Calvinist forces in Scotland. During his trial for High Treason in 1649 Lilburne emphasised the importance and power of a jury’s role in preventing unjust judgments, reading aloud key passages from Sir Edward Coke’s interpretation of Magna Carta.

When the prosecution read out extracts from Lilburne’s pamphlets the public often applauded.

Finding Liliburne ‘not guilty of any crime meriting death’, the jurors were threatened by the Lord Chancellor and required to explain their verdict but they refused. When the jury of London's tradesmen returned their verdict cheers rang out in the court room and celebrations continued all evening, with church bells tolling and the lighting of bonfires. A Medal was struck to commemorate the event.

John Lilburne

John Lilburne was a politically active London apprentice who initially sought greater toleration from the Crown for the Puritan cause in 1639. He was tried by the usually juryless Star Chamber, imprisoned, flogged and placed in pillory stocks after he defended his rights in accordance with the teachings of Edmund Coke. His arguments later got support from Parliament and were decisive in abolishing the Star Chamber by means of the Habeus Corpus Act of 1640.

Lilburne served as a Lieutenant Colonel in the civil war. After King Charles I was defeated in the first civil war Lilburne, by then a Lt .Colonel, became leader of the ‘Levellers’ and sought more broadly based religious toleration and an end to parliamentary corruption. He was the chief author of the Levellers Agreement of the People which in effect challenged the claim that Parliament is the sole representative of the people in the English constitution.

Lilburne argued that English subjects are ’freeborn’ with individual liberties enshrined in Magna Carta. Despite this Parliament later imprisoned him for opposing Cromwell’s attempt to impose an exclusively Presbyterian constitution through his alliance with Calvinist forces in Scotland. During his trial for High Treason in 1649 Lilburne emphasised the importance and power of a jury’s role in preventing unjust judgments, reading aloud key passages from Sir Edward Coke’s interpretation of Magna Carta.

When the prosecution read out extracts from Lilburne’s pamphlets the public often applauded.

Finding Liliburne ‘not guilty of any crime meriting death’, the jurors were threatened by the Lord Chancellor and required to explain their verdict but they refused. When the jury of London's tradesmen returned their verdict cheers rang out in the court room and celebrations continued all evening, with church bells tolling and the lighting of bonfires. A Medal was struck to commemorate the event.

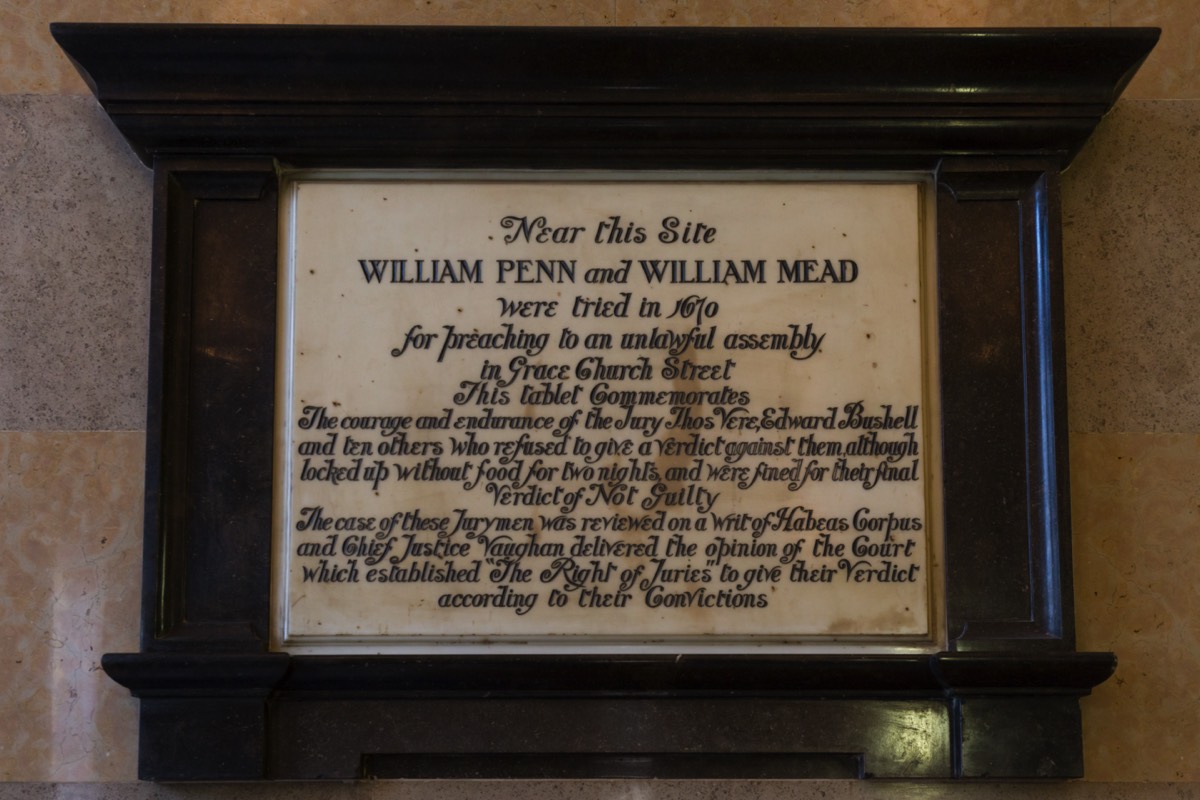

The Trial of William Penn and William Mead

In 1667 William Penn was put on trial for preaching his Quaker faith in public. Whilst admitting to the charge he convinced the jury that they could refuse to convict.

When the jury declined to find Penn and fellow Quaker William Mead guilty in spite of conclusive evidence for a conviction, Lord Chief Justice John Kelynge imprisoned and denied members of the jury daily necessities, including food, fire and even chamber pots, until they rendered a guilty verdict.

In response to a petition for a writ of habeas corpus by Edward Bushel, one of the jurors, Lord Chief Justice Vaughan of the Court of Common Pleas held that a judge may not imprison a jury for refusing to deliver the desired verdict. In doing so he upheld the principle that the jury are judges of both fact and law.

From 1670 following Bushel's case juries could no longer be punished for acquitting a defendant.

In 1688 a trial jury acquitted seven bishops of seditious libel.

In 1667 William Penn was put on trial for preaching his Quaker faith in public. Whilst admitting to the charge he convinced the jury that they could refuse to convict.

When the jury declined to find Penn and fellow Quaker William Mead guilty in spite of conclusive evidence for a conviction, Lord Chief Justice John Kelynge imprisoned and denied members of the jury daily necessities, including food, fire and even chamber pots, until they rendered a guilty verdict.

In response to a petition for a writ of habeas corpus by Edward Bushel, one of the jurors, Lord Chief Justice Vaughan of the Court of Common Pleas held that a judge may not imprison a jury for refusing to deliver the desired verdict. In doing so he upheld the principle that the jury are judges of both fact and law.

From 1670 following Bushel's case juries could no longer be punished for acquitting a defendant.

In 1688 a trial jury acquitted seven bishops of seditious libel.

Plaque at the Old Baily

© Paul Clarke

The Grand Jury as a Shield Against Oppression

In the late 17th century the Grand Jury achieved its reputation as the defender of the liberties of the people and a safeguard against the oppression and despotism of the Crown.

In 1681 Stephen College, an English joiner and activist Protestant, was charged with high treason. An initial Grand Jury refused to indict him although he was later found guilty following a second prosecution.

In 1681 Stephen College, an English joiner and activist Protestant, was charged with high treason. An initial Grand Jury refused to indict him although he was later found guilty following a second prosecution.

In the same year a Grand Jury refused to indict the 1st Earl of Shaftesbury on charges of treason brought by Charles II.

From that point on, the Grand Jury ceased to be an exclusive tool of the crown.

From that point on, the Grand Jury ceased to be an exclusive tool of the crown.

1689 English Bill of Rights

The English Bill of Rights was an act signed into law in 1689 by William III and Mary II, who became co-rulers in England after the overthrow of King James II.

The Bill of Rights stipulated a non-statutory guarantee of the right to trial by jury.

The monarch also undertook not to make laws without the consent of Parliament.

The English Bill of Rights is regarded as the primary law that set the stage for a constitutional monarchy in England.

It is also credited as being an inspiration for the U.S. Bill of Rights.