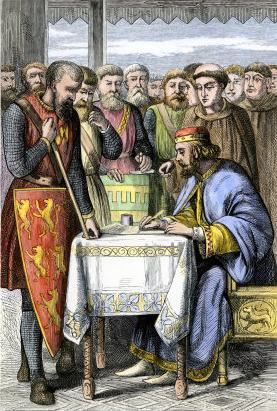

Magna Carta

The English Great Charter was granted by King John on June 15, 1215, under threat of civil war. It was reissued, with alterations, in 1216, 1217, and 1225. It has been acknowledged by some historians as the first national constitution in Europe. England has been described as not merely the first nation state in Europe but as the primary model of the nation state itself - the organisational point of national uniformity which all subsequent modern states to one degree or another sought to emulate and from which they subsequently evolved.

Magna Carta guaranteed the right to judgement by a jury of one’s peers (which was in effect at that time the grand jury) for all subjects ’no matter how humble.’ (ref )

The right to judgement by a jury of your equals was not new, nor even exclusively English, nor was it ‘granted’ by the King to a select group of barons. Juries had been in use across much of Europe within the Merovingian and Carolingian Empires. Magna Carta was a reaffirmation of the Coronation Oath taken by monarchs to uphold the traditional laws of the land as a condition of their right to exercise royal power.

In England this was a recurring practice whereby Anglo-Saxon monarchs undertook to uphold traditional rights, often at Runnymede itself, and predating the very existence of the baronial class. Although Coronation Oaths were fairly common in Europe as a whole, what was new in Magna Carta was the provision that the monarchy could be held accountable to a council of 25 barons - by implication empowered if necessary to use military force - should it fail to uphold the Coronation Oath.

Magna Carta guaranteed the right to judgement by a jury of one’s peers (which was in effect at that time the grand jury) for all subjects ’no matter how humble.’ (ref )

The right to judgement by a jury of your equals was not new, nor even exclusively English, nor was it ‘granted’ by the King to a select group of barons. Juries had been in use across much of Europe within the Merovingian and Carolingian Empires. Magna Carta was a reaffirmation of the Coronation Oath taken by monarchs to uphold the traditional laws of the land as a condition of their right to exercise royal power.

In England this was a recurring practice whereby Anglo-Saxon monarchs undertook to uphold traditional rights, often at Runnymede itself, and predating the very existence of the baronial class. Although Coronation Oaths were fairly common in Europe as a whole, what was new in Magna Carta was the provision that the monarchy could be held accountable to a council of 25 barons - by implication empowered if necessary to use military force - should it fail to uphold the Coronation Oath.

Clause 39

Clause 39 of the Magna Carta of 1215, as translated from the original Latin, provides that:

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land.

This clause was included as Chapter 29 in the 1225 version of Magna Carta and is regarded as England's First Statute.

Clause 39 of the Magna Carta of 1215, as translated from the original Latin, provides that:

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land.

This clause was included as Chapter 29 in the 1225 version of Magna Carta and is regarded as England's First Statute.

It is also recognised as the origin of “due process” in law. That is to say, the idea that the state should treat the accused fairly. It is a much debated concept. In recent centuries people have even questioned whether the right to trial by jury is actually enshrined by this clause, referring specifically to the phrase 'or the law of the land.'

In the early 13th century 'law of the land' referred to a persons' oath. Moreover, as Maitland has pointed out, 'or' - translated from the Latin 'vel' - can also mean ‘and'.

In the early 13th century 'law of the land' referred to a persons' oath. Moreover, as Maitland has pointed out, 'or' - translated from the Latin 'vel' - can also mean ‘and'.

Archbishop Stephen Langton

Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, played a key role in the original drafting of Magna Carta and likely authored the first clause granting the church and its bishops full ecclesiastical freedom. His is the first signature of witness on the document.

His involvement started in 1213 when, after a sermon in St. Paul's Cathedral, he allegedly met privately with some of the barons. At this meeting he revealed that during his studies in Paris he had learned of a charter from 1031, written on the occasion of Henry I's Coronation, in which the King granted the barons specific liberties.

It was with this legal precedent in mind that the barons created a new document which became Magna Carta.

Stephen Langton died in 1228 and was buried in open ground beside the south transept of Canterbury Cathedral - now the Buffs Regimental Chapel.

His involvement started in 1213 when, after a sermon in St. Paul's Cathedral, he allegedly met privately with some of the barons. At this meeting he revealed that during his studies in Paris he had learned of a charter from 1031, written on the occasion of Henry I's Coronation, in which the King granted the barons specific liberties.

It was with this legal precedent in mind that the barons created a new document which became Magna Carta.

Stephen Langton died in 1228 and was buried in open ground beside the south transept of Canterbury Cathedral - now the Buffs Regimental Chapel.

Statue of Stephen Langton,

Archbishop of Canterbury

Photo from the exterior of Canterbury Cathedral

by Ealdgyth

4th Lateran Council and the End of Trial by Ordeal

In the same year as the signing of Magna Carta, after centuries of opposition within the Church the 4th Lateran Council, under Pope Innocent III, finally forbade clerical involvement in trial by ordeal.

Lying behind the ordeal was the principle that God delivered the final ruling. Thus Priests were actively involved in the preparations of such trials with special rituals during the Mass for blessing the instruments of the ordeal.

With the abolition of the Church's role an alternative means of punishment had to be found.

In the same year as the signing of Magna Carta, after centuries of opposition within the Church the 4th Lateran Council, under Pope Innocent III, finally forbade clerical involvement in trial by ordeal.

Lying behind the ordeal was the principle that God delivered the final ruling. Thus Priests were actively involved in the preparations of such trials with special rituals during the Mass for blessing the instruments of the ordeal.

With the abolition of the Church's role an alternative means of punishment had to be found.

The Rise of the Trial Jury

In 1219 Henry III issued a writ to the Eyre justices on how to deal with criminals according to the severity of the crime.

Those accused of grave crimes were to be imprisoned. Those accused of medium crimes were allowed to leave the kingdom. Those accused of lesser crimes could secure pledges for good behaviour and be released. Trials were no longer possible.

No further guidance was offered to the justices and they were left to find a solution for themselves.

The solution to this problem led to development of the trial jury and its separation from the presentment jury which then increasingly became known only as the grand jury.

On the continent however Roman law based upon inquisitorial procedure remained in force unaltered by common law and Magna Carta. Torture was allowed in such law. Consequently while in England jury trial took the place of the ordeal in Europe juries fell in to disuse and were replaced by the inquisitorial method and its use of torture.

The Catholic church established “the” Inquisition in this context. As such, its methods were always looked down upon in England. In fact Henry III banned its use on English soil.

In 1219 Henry III issued a writ to the Eyre justices on how to deal with criminals according to the severity of the crime.

Those accused of grave crimes were to be imprisoned. Those accused of medium crimes were allowed to leave the kingdom. Those accused of lesser crimes could secure pledges for good behaviour and be released. Trials were no longer possible.

No further guidance was offered to the justices and they were left to find a solution for themselves.

The solution to this problem led to development of the trial jury and its separation from the presentment jury which then increasingly became known only as the grand jury.

On the continent however Roman law based upon inquisitorial procedure remained in force unaltered by common law and Magna Carta. Torture was allowed in such law. Consequently while in England jury trial took the place of the ordeal in Europe juries fell in to disuse and were replaced by the inquisitorial method and its use of torture.

The Catholic church established “the” Inquisition in this context. As such, its methods were always looked down upon in England. In fact Henry III banned its use on English soil.

Writ de Odio et Atia

If a defendant asserted that the person bringing the charge against them was acting out of spite and hatred they could purchase a writ de odio et atia to have their case referred to a verdict of twelve jurors.

This provision was inserted into Magna Carta as Article 36.

How did Juries Replace Trial by Ordeal?

The use of juries in judicial procedure had been accepted for centuries before Magna Carta.

Trial by jury or the verdict of 12 recognitors (jurors) was an established mode of proof for writs under Henry II. If a defendant asserted that the person bringing the charge against them was acting out of spite and hatred they could purchase a writ de odio et atia to have their case referred to a verdict of twelve jurors.

The use of juries in judicial procedure had been accepted for centuries before Magna Carta.

Trial by jury or the verdict of 12 recognitors (jurors) was an established mode of proof for writs under Henry II. If a defendant asserted that the person bringing the charge against them was acting out of spite and hatred they could purchase a writ de odio et atia to have their case referred to a verdict of twelve jurors.

The Grand Assize and writs de odio et atia demonstrated that defendants were willing to choose to abide by the decision of men over the divine judgement of God.

By 1212 presentment juries had already developed a power to issue verdicts in so far as they decided which accused persons could be sent to the ordeal.

These facts resulted in a shift in opinion within the legal establishment: if juries could decide in these cases why could they not decide if a prisoner was guilty or not?

Nevertheless initially judges were wary of allowing juries to decided guilt. Where the presentment jury was the same as the trial jury it removed a step from the judicial process. The defendant lost the chance to save himself by ordeal and justices were reluctant to leave a defendant's guilt to his neighbours rather that the will of God.

After some years of hesitation however justices realised that if a jury could decide malicious claims then there was no reason why a jury couldn't decide guilt or innocence.

At first justices exercised discretion over making up the trial jury. It could be the presentment jury whilst on other occasions there is evidence of 84 person juries. Sometimes different juries attending the Eyre gave their verdicts separately upon which the court made a judgement.

According to Bracton (c.1210-1268) the practice developed whereby the accused was first heard by the hundred jury. If they suspected him he went before a larger jury of four men plus the reeve from each of the four vills nearest to the crime. In this manner thirty two people had to agree if the prisoner was guilty. The trial jury was larger than the presentment jury.

By the mid 13th century justices would chose twelve jurors from those present at the court, rather than taking verdicts from numerous vills and hundreds. They could be members of the presentment jury because the principle of jury trial was to get information from those who had it.

By 1212 presentment juries had already developed a power to issue verdicts in so far as they decided which accused persons could be sent to the ordeal.

These facts resulted in a shift in opinion within the legal establishment: if juries could decide in these cases why could they not decide if a prisoner was guilty or not?

Nevertheless initially judges were wary of allowing juries to decided guilt. Where the presentment jury was the same as the trial jury it removed a step from the judicial process. The defendant lost the chance to save himself by ordeal and justices were reluctant to leave a defendant's guilt to his neighbours rather that the will of God.

After some years of hesitation however justices realised that if a jury could decide malicious claims then there was no reason why a jury couldn't decide guilt or innocence.

At first justices exercised discretion over making up the trial jury. It could be the presentment jury whilst on other occasions there is evidence of 84 person juries. Sometimes different juries attending the Eyre gave their verdicts separately upon which the court made a judgement.

According to Bracton (c.1210-1268) the practice developed whereby the accused was first heard by the hundred jury. If they suspected him he went before a larger jury of four men plus the reeve from each of the four vills nearest to the crime. In this manner thirty two people had to agree if the prisoner was guilty. The trial jury was larger than the presentment jury.

By the mid 13th century justices would chose twelve jurors from those present at the court, rather than taking verdicts from numerous vills and hundreds. They could be members of the presentment jury because the principle of jury trial was to get information from those who had it.

Edward I (1272- 1307)

Erected at Westminster Abbey sometime during reign of Edward I, thought to be an image of the King.

1st Statute of Westminster (1275)

Initially courts were reluctant to compel jury trial but there were few alternatives.

If a prisoner refused to consent to trial by jury the court could exercise discretion by choosing a larger jury to hear the case; allow the prisoner to leave the kingdom or allow them to purchase sureties to guarantee their future good behaviour.

Only in 1275 did the crown feel empowered to impose trial by jury as the common law of the land for notorious felons although the accused still had to consent to 'put themselves upon the country'.

Initially courts were reluctant to compel jury trial but there were few alternatives.

If a prisoner refused to consent to trial by jury the court could exercise discretion by choosing a larger jury to hear the case; allow the prisoner to leave the kingdom or allow them to purchase sureties to guarantee their future good behaviour.

Only in 1275 did the crown feel empowered to impose trial by jury as the common law of the land for notorious felons although the accused still had to consent to 'put themselves upon the country'.

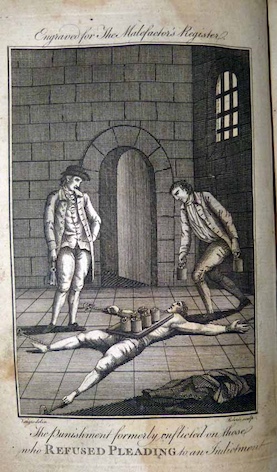

Peine forte et dure

If prisoners refused jury trial the Statute directed that the accused was to be kept provisionally in prison forte et dure. This was later corrupted into peine forte et dure whereby in the 16th century prisoners had weights placed upon them until they agreed to jury trial or died (a practice abolished in 1772 when a refusal to plead became a conviction. Not guilty pleas weren't accepted until 1827).

The incentive for a prisoner to refuse jury trial lay in the fact that if they died in prison and weren't convicted their property wasn't forfeited to the Crown but passed to their heirs.

If prisoners refused jury trial the Statute directed that the accused was to be kept provisionally in prison forte et dure. This was later corrupted into peine forte et dure whereby in the 16th century prisoners had weights placed upon them until they agreed to jury trial or died (a practice abolished in 1772 when a refusal to plead became a conviction. Not guilty pleas weren't accepted until 1827).

The incentive for a prisoner to refuse jury trial lay in the fact that if they died in prison and weren't convicted their property wasn't forfeited to the Crown but passed to their heirs.