Roman Britain

Roman Britain

In 55 B.C. Julius Caesar led the first Roman invasion of Britain. However it wasn't until 53 A.D. when Emperor Claudius occupied Britain and added it to the Roman Empire.

The conquering Romans established military centres and roads, imposed taxes, and organised the government without enslaving the native peoples. It was primarily a military occupation.

The majority of Roman Britain's inhabitants were subsistence farmers whose lives changed little during Roman rule. The Britons were the least Romanised of all the Western peoples in the Roman Empire.

Roman Britain was divided into two broad zones. In the flat, fertile south east, about 40 major urban centres had all the trappings of a Roman colony including forums, baths and villas. Both Romans and more affluent Britons wore Roman dress and spoke Latin. Christianity arrived in the 3rd century and many Britons converted.

To the north and west the hilly, rocky land was less suited to Roman settlement and agriculture and the tribes were less cooperative. The settlements were mainly fortresses occupied by Roman soldiers.

In 55 B.C. Julius Caesar led the first Roman invasion of Britain. However it wasn't until 53 A.D. when Emperor Claudius occupied Britain and added it to the Roman Empire.

The conquering Romans established military centres and roads, imposed taxes, and organised the government without enslaving the native peoples. It was primarily a military occupation.

The majority of Roman Britain's inhabitants were subsistence farmers whose lives changed little during Roman rule. The Britons were the least Romanised of all the Western peoples in the Roman Empire.

Roman Britain was divided into two broad zones. In the flat, fertile south east, about 40 major urban centres had all the trappings of a Roman colony including forums, baths and villas. Both Romans and more affluent Britons wore Roman dress and spoke Latin. Christianity arrived in the 3rd century and many Britons converted.

To the north and west the hilly, rocky land was less suited to Roman settlement and agriculture and the tribes were less cooperative. The settlements were mainly fortresses occupied by Roman soldiers.

Emperor Claudius

The province of Britannia was governed for the emperor by a legate, an ex-consul of the highest, senatorial rank who also commanded the armed forces in the island. He was supreme judge, hearing disputes involving Roman citizens and individuals of high social status.

The procurator handled the provincial finances.

The legate and procurator had little administrative support and the work of government and justice was devolved to local government in the cities.

These civic units, run by loyal local aristocracies, were the basic instrument of Roman rule throughout the empire.

Each was governed by a town council (curia), led by elected magistrates. They were responsible for settling local disputes and collecting taxes and passing them on to the state.

Barbarian Invasions

In the 3rd century Britain began to be attacked by Barbarians. From the west there were raiders from Ireland known as the Scotti. Raiders from Germanic speaking tribes attacked the east and south coasts.

Although the Barbarians were initially defeated in 410 A.D. the Roman legions in Britain were ordered to withdraw to the continent.

Trial by Jury for Misconduct in Public Office

Trial by Jury in Ancient Rome

The institution of trial by jury played an important part in the legal system of the Roman world and can be traced back to a series of enactments passed by the Roman comitia, or popular assembly, dating from 149 B.C.

The most important aspect of this new court of inquiry was a body of jurors, a miniature popular assembly, to determine the guilt or innocence of a person charged with crimes of misconduct while holding public office in the provinces.

Before 149 B.C. Roman citizens were tried before the entire body of their fellow citizens assembled in the comitia.

Complaints made by non-citizens concerning the misconduct of Roman magistrates in the provinces had to be brought to the attention of the Roman Senate by special ambassadors. The Roman Senate could, and often did, refuse to listen to these complaints.

Following lex Calpurnia in 149B.C. and lex Acilia c.122 B.C. a special body of jurors, consilium iudicum, was chosen to decide upon the guilt or liability of a defendant charged with misconduct in public office.

The purpose of this new procedure was to provide better administration of justice throughout the Roman Empire.

These extraordinary courts were intended to protect the inhabitants of the Roman provinces from widespread extortion and the taking of money by predatory Roman officials.

The institution of trial by jury played an important part in the legal system of the Roman world and can be traced back to a series of enactments passed by the Roman comitia, or popular assembly, dating from 149 B.C.

The most important aspect of this new court of inquiry was a body of jurors, a miniature popular assembly, to determine the guilt or innocence of a person charged with crimes of misconduct while holding public office in the provinces.

Before 149 B.C. Roman citizens were tried before the entire body of their fellow citizens assembled in the comitia.

Complaints made by non-citizens concerning the misconduct of Roman magistrates in the provinces had to be brought to the attention of the Roman Senate by special ambassadors. The Roman Senate could, and often did, refuse to listen to these complaints.

Following lex Calpurnia in 149B.C. and lex Acilia c.122 B.C. a special body of jurors, consilium iudicum, was chosen to decide upon the guilt or liability of a defendant charged with misconduct in public office.

The purpose of this new procedure was to provide better administration of justice throughout the Roman Empire.

These extraordinary courts were intended to protect the inhabitants of the Roman provinces from widespread extortion and the taking of money by predatory Roman officials.

Foreign Influences on the Lex Acilia

This new procedure addressing justice for non-citizens was greatly influenced by foreign laws and customs.

Lex Acilia was an essential part of the judicial reforms introduced by Gaius Gracchus (c. 154 -121BC).

It's main legal and procedural innovations in all probability had their origin in Ancient Athenian criminal procedure.

This institution was analogous to the later Anglo-Saxon jury system.

Trial by jury was applied only to the specific crime of misconduct in public office in the provinces brought by non-citizens of Rome. It was never extended further in the Roman legal system.

This new procedure addressing justice for non-citizens was greatly influenced by foreign laws and customs.

Lex Acilia was an essential part of the judicial reforms introduced by Gaius Gracchus (c. 154 -121BC).

It's main legal and procedural innovations in all probability had their origin in Ancient Athenian criminal procedure.

This institution was analogous to the later Anglo-Saxon jury system.

Trial by jury was applied only to the specific crime of misconduct in public office in the provinces brought by non-citizens of Rome. It was never extended further in the Roman legal system.

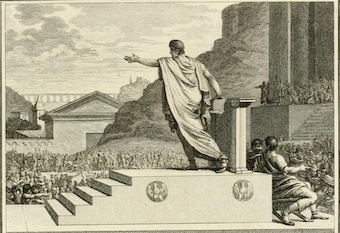

Gaius Gracchus tribune of the people presiding over the Plebeian Council

The Functions of the Prosecutor or Plaintiff

Once the trial was set the plaintiff was granted sufficient time to collect evidence - witnesses or written documents - to support his charges.

Since as a rule the defendant did not commit the crime in Rome or Italy the collecting of evidence was usually connected with travel abroad. Thus the plaintiff might go to the province where the defendant had committed the crime to collect the evidence and interview persons or magistrates.

He could appear before the assemblies in these provincial communities and persuade them to pass resolutions in which the opinion of the community concerning the defendant was expressed.

Once the trial was set the plaintiff was granted sufficient time to collect evidence - witnesses or written documents - to support his charges.

Since as a rule the defendant did not commit the crime in Rome or Italy the collecting of evidence was usually connected with travel abroad. Thus the plaintiff might go to the province where the defendant had committed the crime to collect the evidence and interview persons or magistrates.

He could appear before the assemblies in these provincial communities and persuade them to pass resolutions in which the opinion of the community concerning the defendant was expressed.

The Empanelling of the Jurors

Twenty days after an indictment the plaintiff chose one hundred persons from the 'year list' of four hundred and fifty jurors. He had to identify all those jurors to whom he was related either by blood or marriage or with whom he had any business or professional relation. These persons were declared ineligible for jury duty in this particular trial. Members of the same family were also prevented from serving as jurors on the same trial.

Within sixty days of the indictment the defendant chose fifty jurors from the list of one hundred proposed by the plaintiff. Should the defendant fail to make this choice within the prescribed period he forfeited this privilege and the plaintiff selected the final fifty jurors.

The names of these fifty jurors, together with the names of the two parties and the patroni chosen to assist the plaintiffs in their cause, were published on tables and displayed for the duration of the trial.

This system of empanelling jurors was later superseded by a system by which the jurors were chosen by lot.

The body of the final fifty jurors constituted primarily a 'fact finding board.' They voted on the guilt or innocence of the defendant and also decided the damages to be paid. In all his actions the presiding magistrate was bound by the opinions of this consilium.

Twenty days after an indictment the plaintiff chose one hundred persons from the 'year list' of four hundred and fifty jurors. He had to identify all those jurors to whom he was related either by blood or marriage or with whom he had any business or professional relation. These persons were declared ineligible for jury duty in this particular trial. Members of the same family were also prevented from serving as jurors on the same trial.

Within sixty days of the indictment the defendant chose fifty jurors from the list of one hundred proposed by the plaintiff. Should the defendant fail to make this choice within the prescribed period he forfeited this privilege and the plaintiff selected the final fifty jurors.

The names of these fifty jurors, together with the names of the two parties and the patroni chosen to assist the plaintiffs in their cause, were published on tables and displayed for the duration of the trial.

This system of empanelling jurors was later superseded by a system by which the jurors were chosen by lot.

The body of the final fifty jurors constituted primarily a 'fact finding board.' They voted on the guilt or innocence of the defendant and also decided the damages to be paid. In all his actions the presiding magistrate was bound by the opinions of this consilium.

Jury Proceedings

Under the provisions of the lex Acilia the jurors had two main tasks to perform: the iudicatio, and the litis aestimatio.

In the iudicatio the defendant was either found guilty or was acquitted based upon a general finding of the jury. If the defendant appeared to be guilty and the general evidence submitted warranted a continuation of the whole procedure it proceeded to the second stage, litis aestimatio, when the individual charges were examined in more detail.

It was quite possible that in this second stage that all individual charges might be rejected. Thus a case might arise where the defendant appeared to be guilty of the general charge of having taken money illegally, but on closer scrutiny was acquitted of the particular and more detailed charges and hence was not found guilty at all.

In this sense the iudicatio very much resembled the finding of a grand jury while the litis aestimatio amounted to a regular jury trial.

Under the provisions of the lex Acilia the jurors had two main tasks to perform: the iudicatio, and the litis aestimatio.

In the iudicatio the defendant was either found guilty or was acquitted based upon a general finding of the jury. If the defendant appeared to be guilty and the general evidence submitted warranted a continuation of the whole procedure it proceeded to the second stage, litis aestimatio, when the individual charges were examined in more detail.

It was quite possible that in this second stage that all individual charges might be rejected. Thus a case might arise where the defendant appeared to be guilty of the general charge of having taken money illegally, but on closer scrutiny was acquitted of the particular and more detailed charges and hence was not found guilty at all.

In this sense the iudicatio very much resembled the finding of a grand jury while the litis aestimatio amounted to a regular jury trial.