Anglo Saxon Justice

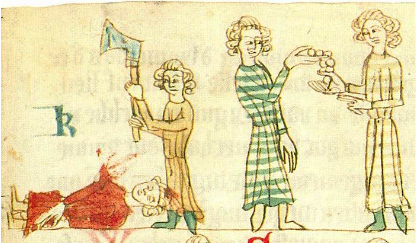

In early tribal societies justice was based on the blood feud. When a member of a kinship group was injured, the whole family avenged it. Wergild replaced this old system of retaliation and endless feud.

Under wergild if a person was injured or killed, the guilty party would pay the victim or their survivors a fine based on the severity of the damage and the status of the victim. Once paid the feud was ended and further retaliation was not regarded as justifiable, becoming instead a breach of the king's peace.

Under wergild if a person was injured or killed, the guilty party would pay the victim or their survivors a fine based on the severity of the damage and the status of the victim. Once paid the feud was ended and further retaliation was not regarded as justifiable, becoming instead a breach of the king's peace.

Wergild

Paying wergild was the responsibility of the perpetrator’s entire family or kinship group.

The ability of the kinship group to oust troublesome members was a strong check on criminal behaviour. A habitual criminal might find himself declared an ‘outlaw’ by his kinship group and he would be left without any help to pay wergild and without anyone to defend and protect him.

At a later stage, the joint responsibility of the kinsfolk gave place to the joint responsibility of the district or group of householders which formed a tithing.

The ability of the kinship group to oust troublesome members was a strong check on criminal behaviour. A habitual criminal might find himself declared an ‘outlaw’ by his kinship group and he would be left without any help to pay wergild and without anyone to defend and protect him.

At a later stage, the joint responsibility of the kinsfolk gave place to the joint responsibility of the district or group of householders which formed a tithing.

Codes of Law or DOOMS

Kings started to write down Codes of Law or dooms around the time they converted to Christianity, when literacy was becoming more common.

But the laws dated to before the Anglo-Saxon migration. The idea was that kings were codifying law that already existed i.e. the law and established customs of the people which had been passed on orally.

Codes of law were produced at regular intervals by kings and provided an opportunity to add new statutes, modify existing ones or re-state old laws that were being ignored.

Kings started to write down Codes of Law or dooms around the time they converted to Christianity, when literacy was becoming more common.

But the laws dated to before the Anglo-Saxon migration. The idea was that kings were codifying law that already existed i.e. the law and established customs of the people which had been passed on orally.

Codes of law were produced at regular intervals by kings and provided an opportunity to add new statutes, modify existing ones or re-state old laws that were being ignored.

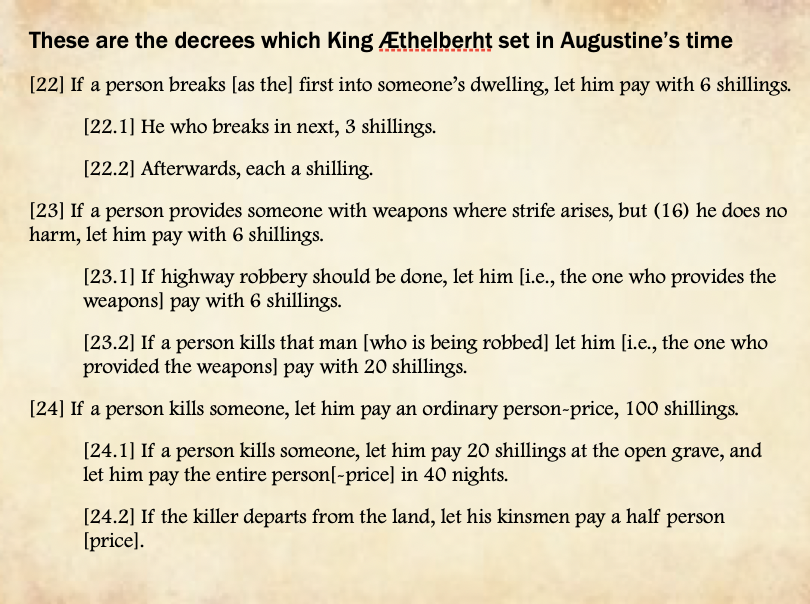

Aethelberht's Law Code

Aethelberht was the King of Kent from around 589 until his death in 616. He is referred to as the third bretwalda, or 'Britain-ruler' by Bede. He was the first Anglo Saxon king to convert to Christianity c.601, influenced by his Frankish wife Bertha and the arrival of Augustine in 597.

Aethelberht's Law Code is thought to be the earliest example of a document written in Old English and records local customs and laws which had previously been passed down orally.

The Law Code is a list of 90 dooms or judgments. The initial provisions of the code offer protection to the church. These are followed by the wergild compensations to be paid arranged according to social rank descending from king to slave.

It has been suggested that Aethelberht had been impressed by the Roman system of law brought by the missionaries of Rome and wished to write his own code of law. His conversion to Christianity brought him access to the Church and with it literacy. Since the Church was keen to write down the grants of land given them they were keen to help establish a written legal code.

This very early code became the grounding for Kentish law. Subsequent Kings of the 7th century such as Hlothar, Eadric and Wihtred followed this example and added approximately 50 new dooms to the original list of 90.

Aethelberht was the King of Kent from around 589 until his death in 616. He is referred to as the third bretwalda, or 'Britain-ruler' by Bede. He was the first Anglo Saxon king to convert to Christianity c.601, influenced by his Frankish wife Bertha and the arrival of Augustine in 597.

Aethelberht's Law Code is thought to be the earliest example of a document written in Old English and records local customs and laws which had previously been passed down orally.

The Law Code is a list of 90 dooms or judgments. The initial provisions of the code offer protection to the church. These are followed by the wergild compensations to be paid arranged according to social rank descending from king to slave.

It has been suggested that Aethelberht had been impressed by the Roman system of law brought by the missionaries of Rome and wished to write his own code of law. His conversion to Christianity brought him access to the Church and with it literacy. Since the Church was keen to write down the grants of land given them they were keen to help establish a written legal code.

This very early code became the grounding for Kentish law. Subsequent Kings of the 7th century such as Hlothar, Eadric and Wihtred followed this example and added approximately 50 new dooms to the original list of 90.

Statute of King Aethelberht

Canterbury Cathedral

Statute of Queen Bertha

Lady Wootton's Green, Canterbury

Statute of King Aethelberht

Lady Wootton's Green, Canterbury

Friborh or Frankpledge

Friborh, later known as Frankpledge, was a system of community policing and surety - borh meaning security or surety.

A master was borh for his servants. Each householder was answerable for the behaviour of his family, slaves and guests of more than three days. Gilds formed where members undertook to be borh for the brethren. Tithings were responsible for their members.

King Cnut required subjects to be in a tithing [II Cnut, 20] and any person who did not register in a tithing was punished as an outlaw. To change membership of a tithing required a warrant or certificate from the original Tithingman or Borhsholder.

Once a year every person was obliged to show the Hundred which Tithing they belonged to. The Sheriff would administer membership of the Tithings at the bi-annual tourns.

Friborh, later known as Frankpledge, was a system of community policing and surety - borh meaning security or surety.

A master was borh for his servants. Each householder was answerable for the behaviour of his family, slaves and guests of more than three days. Gilds formed where members undertook to be borh for the brethren. Tithings were responsible for their members.

King Cnut required subjects to be in a tithing [II Cnut, 20] and any person who did not register in a tithing was punished as an outlaw. To change membership of a tithing required a warrant or certificate from the original Tithingman or Borhsholder.

Once a year every person was obliged to show the Hundred which Tithing they belonged to. The Sheriff would administer membership of the Tithings at the bi-annual tourns.

Compurgation

When a person was accused of a crime they had two main ways to prove their innocence. The first was by compurgation.

When factual evidence was not conclusive the accused person swore an oath of innocence and produced a number of people, called oath-helpers, to support their claim and act as character witnesses.

The basic principle of the law was that 'denial is always stronger than accusation', so in most cases the defendant would be allowed to bring forward an oath to prove his innocence.

This was achieved with the aid of compurgators or oath-helpers. The number required depended on the seriousness of the crime and the importance of the victim. The value of a compurgator's oath was also dependent on their social position.

These oath-helpers were not required to give any evidence or information. They did not swear to the facts of the case but to the credibility of the accused person. The theory was that people were essentially honest either by nature or the fear of retribution.

A man who was known to be guilty would have a hard job getting together oath-helpers.

When a person was accused of a crime they had two main ways to prove their innocence. The first was by compurgation.

When factual evidence was not conclusive the accused person swore an oath of innocence and produced a number of people, called oath-helpers, to support their claim and act as character witnesses.

The basic principle of the law was that 'denial is always stronger than accusation', so in most cases the defendant would be allowed to bring forward an oath to prove his innocence.

This was achieved with the aid of compurgators or oath-helpers. The number required depended on the seriousness of the crime and the importance of the victim. The value of a compurgator's oath was also dependent on their social position.

These oath-helpers were not required to give any evidence or information. They did not swear to the facts of the case but to the credibility of the accused person. The theory was that people were essentially honest either by nature or the fear of retribution.

A man who was known to be guilty would have a hard job getting together oath-helpers.

Trial by Ordeal

Sometimes, a defendant might not be considered 'oath-worthy' if he had a record of committing crimes or if he had been caught in the act or with stolen goods.

If the plaintiff had been given the oath, or if it had been granted to the defendant and he had failed to find enough oath-helpers, the defendant might then go to the ordeal, the judgement of God, rather than admit to his guilt.

The Church was responsible for administering the ordeal, which was preceded by a three-day fast and a Mass in which the accused was given the opportunity to confess. If he still maintained his innocence he was able to decide between the ordeals of water or iron.

In the ordeal of hot water the accused had to plunge his hand into boiling water to take out a stone.

In the ordeal of iron the accused had to carry a glowing iron bar nine feet.

In both of these, the accused's hand was bandaged, and if the wound was healing cleanly, without festering, after three days, he was judged innocent.

In the ordeal of cold water the accused was given holy water to drink, then thrown into the river. The guilty floated, while the innocent sank.

An ordeal said to be preserved specifically for the clergy was ordeal by accursed morsel. The accused was required to eat a piece of meat with a feather or other foreign body in it and was adjudged guilty if he choked.

Sometimes, a defendant might not be considered 'oath-worthy' if he had a record of committing crimes or if he had been caught in the act or with stolen goods.

If the plaintiff had been given the oath, or if it had been granted to the defendant and he had failed to find enough oath-helpers, the defendant might then go to the ordeal, the judgement of God, rather than admit to his guilt.

The Church was responsible for administering the ordeal, which was preceded by a three-day fast and a Mass in which the accused was given the opportunity to confess. If he still maintained his innocence he was able to decide between the ordeals of water or iron.

In the ordeal of hot water the accused had to plunge his hand into boiling water to take out a stone.

In the ordeal of iron the accused had to carry a glowing iron bar nine feet.

In both of these, the accused's hand was bandaged, and if the wound was healing cleanly, without festering, after three days, he was judged innocent.

In the ordeal of cold water the accused was given holy water to drink, then thrown into the river. The guilty floated, while the innocent sank.

An ordeal said to be preserved specifically for the clergy was ordeal by accursed morsel. The accused was required to eat a piece of meat with a feather or other foreign body in it and was adjudged guilty if he choked.

Administering Justice

When differences arose within a community the Borhsholder would summon the whole Tithing to assist in finding a solution.

Controversies between members of different Tithings were brought before the Hundred which assembled regularly every four weeks. Twelve freeholders were chosen and sworn together with the Hundreder of that division to administer impartial justice. Some scholars believe that this method of decision making comprised the origin of juries.

When differences arose within a community the Borhsholder would summon the whole Tithing to assist in finding a solution.

Controversies between members of different Tithings were brought before the Hundred which assembled regularly every four weeks. Twelve freeholders were chosen and sworn together with the Hundreder of that division to administer impartial justice. Some scholars believe that this method of decision making comprised the origin of juries.