Ancient Athenian Democracy

The Popular Courts and Constitutional Juries

The first constitutional juries in history were those of ancient Greece in the first millennium B.C.

The Athenian leader Solon [c. 630 – c. 560 B.C.] introduced them as the cornerstone of state organisation by establishing the court of last appeal as a large jury. These courts involved at least 201 jurors and could have as many as 2,500.

The popular courts heard a variety of cases. They played an important constitutional role by interpreting the laws, decrees, and decisions passed by the Ekklesia, Boule, and archons.

The Athenian city state also decreed that any person failing to report suspected wrongdoing in government would be guilty of negligence as a citizen.

The first constitutional juries in history were those of ancient Greece in the first millennium B.C.

The Athenian leader Solon [c. 630 – c. 560 B.C.] introduced them as the cornerstone of state organisation by establishing the court of last appeal as a large jury. These courts involved at least 201 jurors and could have as many as 2,500.

The popular courts heard a variety of cases. They played an important constitutional role by interpreting the laws, decrees, and decisions passed by the Ekklesia, Boule, and archons.

The Athenian city state also decreed that any person failing to report suspected wrongdoing in government would be guilty of negligence as a citizen.

Ecclesia: assembly of citizens in a city-state.

Boule: a council of over 500 citizens appointed to run daily affairs of the city. Originally a council of nobles advising a king the boule evolved according to the constitution of the city.

Archon: the chief magistrate or magistrates in many city-states.

Boule: a council of over 500 citizens appointed to run daily affairs of the city. Originally a council of nobles advising a king the boule evolved according to the constitution of the city.

Archon: the chief magistrate or magistrates in many city-states.

Thetes were the lowest order of freeman in ancient Athens. Plutarch explains their participation in the popular courts from the time of Solon:

All the rest were called Thetes ; they were not allowed to hold any office but took part in the administration only as members of the Assembly and as jurors.

This last privilege seemed at first of no account, but afterwards proved to be of the very highest importance, since most disputes finally came into the hands of these jurors.

For even in cases which Solon assigned to the magistrates for decision, he allowed also an appeal to a popular court when anyone desired it.

Besides, it is said that his laws were obscurely and ambiguously worded on purpose, to enhance the power of the popular courts. For since parties to a controversy could not get satisfaction from the laws, the result was that they always wanted jurors to decide it, and every dispute was laid before them, so that they were in a manner masters of the laws.

(From The Parallel Lives by Plutarch, Life of Solon Part 18.2)

Jury Selection

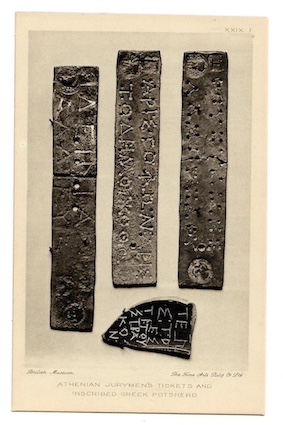

At the beginning of the year jurors were chosen for jury duty from a large body of citizens. Each juror was given a bronze pinakion inscribed with his name, father's name and deme/tribe.

These pinakia were used in a kleroteria in order to assign jurors to the courts.

The kleroterion was a slab of stone incised with rows of slots. According to Aristotle, a pair of such kleroteria stood at the entrance to each court.

[From The Athenian Constitution by Aristotle, Part 63]

At the beginning of the year jurors were chosen for jury duty from a large body of citizens. Each juror was given a bronze pinakion inscribed with his name, father's name and deme/tribe.

These pinakia were used in a kleroteria in order to assign jurors to the courts.

The kleroterion was a slab of stone incised with rows of slots. According to Aristotle, a pair of such kleroteria stood at the entrance to each court.

[From The Athenian Constitution by Aristotle, Part 63]

Kleroteria

On the day of a trial a potential juror would appear before the magistrate in charge and place his pinakion in his tribe's basket at the base of the kleroterion.

The pinakia were placed randomly in the slots so that every member of a tribe had their tokens placed in the same column.

Attached to the kleroterion was a hollow bronze tube which could be fed different coloured marbles - assumed to be black and white.

A turn of an attached mechanism produced a single ball. If it was white, the ten citizens whose pinakia were placed on the first horizontal row would be assigned to the jury for that day. If a black ball was released the citizens whose pinakia were in that row were dismissed.

The machine assured random selection both in the order in which the pinakia were placed in the kleroterion and in the order in which the balls appeared. It also guaranteed equal representation for each tribe in every court.

It demonstrates the lengths to which the Athenians went to ensure both equality and forestall corruption in their governmental affairs.

There was no easy way to bribe an Athenian jury, made up of at least 201 men chosen immediately before the court sat.

The Speakers

Litigants at a trial spoke on their own behalf, although occasionally they used speeches prepared by trained professionals.

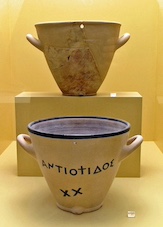

No trial took more than a single day. Time was allotted to the speakers according to a set schedule and measured carefully by means of klepsydrai or waterclocks.

[Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 672]

Klepsydra [Waterclock]

Reconstruction of a clay original from Athenian Agora

The Verdict

After the speeches and other evidence had been presented the jury voted by casting ballots.

After the speeches and other evidence had been presented the jury voted by casting ballots.

Payment of Jurors

Athenian jurors were paid. This democratic procedure was designed to ensure that all citizens could afford to serve.

Athenian jurors were paid. This democratic procedure was designed to ensure that all citizens could afford to serve.

Ancient Athenian Jurors’ Ballots

Aristotle on how the jury voted in the mid 4th century B.C.

[From The Athenian Constitution by Aristotle, Part 68]

[From The Athenian Constitution by Aristotle, Part 68]

There are bronze ballots, with an axle through the middle, half of them hollow and half solid.

When the speeches have been made, the men appointed by lot to take charge of the ballots give each juror two ballots, one hollow and one solid, in full view of the litigants so that no one shall take two solid or two hollow...

There are two jars in the court, one of bronze and one of wood....

The jurors cast their votes in these: the bronze jar counts and wooden does not; the bronze one has a pierced attachment through which only one ballot can pass, so that one man cannot cast two votes.

When the jurors are ready to vote, the herald first makes a proclamation, to ask whether the litigants object to the testimonies: objections are not allowed once the voting has begun.

Then he makes another proclamation: 'The hollow ballot is for the litigant who spoke first (prosecutor), the solid for the one who spoke afterwards (defendant).

The juror takes his ballots together from the stand, gripping the axle of the ballot and not showing the contestants which is the hollow and which is the solid, and drops the one that is to count into the bronze jar and the one that is not into the wooden.